Worldbuilding in fantasy and science fiction is a huge part of the genre. Every book or series introduces a reader to a new set of rules, such as, dragons exist in this world, or some people are born with magical powers. The mundane details are just as important as the fantastic ones. Is this a kingdom? Are some of the population serfs? How is order maintained? What are the threats faced by the people of this book? Poverty, famine, bandits? Have veteran soldiers been marauding since the war ended? What is proscribed and what is legal? All these questions need answers. Sometimes the smaller details can root the reader in the setting and give a sense of realness, even in genres that concern themselves with technology that may not exist yet, or with giant, telepathic, flying reptiles. Every first book in a series is a little like a superhero origin movie, not just for the characters (who may well have extraordinary powers), but for the setting of the book itself, too. This provides a challenge for the writer (but it’s an enjoyable one I like to think).

For me, the continent of Vinterkveld, where the story that begins in Witchsign plays out, was always meant to be analogous with Scandinavian countries and Russia. I wanted to tell a story in a world where the weather was as unforgiving as those who ruled. I wanted ominous pine forests, looming mountains and forbidding skies that threaten rain or sleet. Eastern European countries have a wealth of folklore and deities, which I have borrowed and altered. My previous series was set in a Gormenghast-esque castle, heavily influenced by the Italian Renaissance. Vinterkveld provided me with a chance to write a more classic ‘fantasy’ series in the spirit of The Lord of the Rings – if only in terms of geography.

Brian W. Aldiss once said that it was science fiction that held up a mirror to the present, and it has been a conscious decision of mine to try and touch on modern themes, even in a genre that usually lurks in an imagined, pre-industrial, feudal era (fantasy). Women in fantasy don’t often enjoy an easy time (on and off the page). In this way, the genre holds a mirror up to the present both in terms of treatment and representation. It was important to me to feature many female characters, rather than the token two or three, in the world that I built. I was also keen to avoid some often-seen pitfalls (such as the normalisation of sexual assault and rather indulgent descriptions of the female form).

After all, if we can imagine dragons and enchanted weapons, is it so hard to imagine a more equal society? You alone can be the judge of whether I succeeded.

The persecution of those who are unlike ourselves is a bigger feature of the book. Forbidden magic is an established trope in fantasy and one that I wanted to write with a twist. My initial thought for Witchsign was ‘what happened if Harry Potter ended up at Soviet Hogwarts and was found out as a Muggle?’ Persecution is sadly not confined to books. It’s small wonder it remains such a vital topic at a time of rising tensions, anti-Semitism, and state-sanctioned hostility toward immigrants. Steiner, one of two main characters in Witchsign goes to extraordinary lengths to protect his sister from the Empire’s Holy Synod, an organisation charged with capturing, policing and exploiting magic-using children.

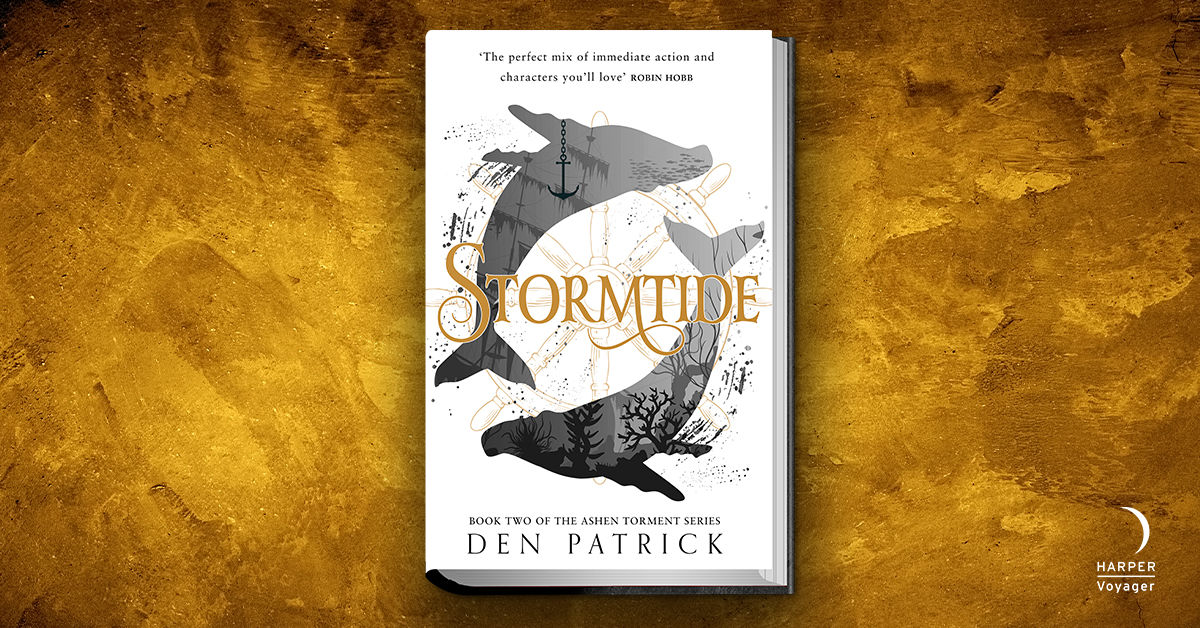

The Ashen Torment is a YA-ish fantasy series in a similar vein to Joe Abercrombie’s Shattered Sea books and has won plaudits from writers such as Pete Newman, Jen Williams, and Robin Hobb. But don’t take their word for it, explore Vinterkveld for yourself.

Stormtide is released on 30 May 2019 and forms the second part of The Ashen Torment series.

Den Patrick lives in London with his wife and two cats, Neville and Luna. His first novel, The Boy with the Porcelain Blade (2014), was nominated for the Best Newcomer award by the British Fantasy Society.